Psychedelics and Chronic Pain

Psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin are gaining legitimacy as potential treatments for depression, anxiety, and even chronic pain. This post summarizes some basic evidence and theoretical explanations for why they might help.

The short answer is that chronic pain, depression, and anxiety are to some extent caused by persistent maladaptive "habits" of the brain, and psychedelics may create the "neural flexibility" that is needed to break them.

Disclaimer: Nothing I say here means you should try psychedelics as a way to help with your pain. Although they may have benefit, they also have risks.

Renewed interest in psychedelics

Psychedelics have been used by humans to change states of mind for a long time. Science got interested in the 1930s, very interested in the 1960s, and then had to cool it for a few decades because of negative associations with the counterculture, and also the fact that the drugs were illegal. Recently, the social and legal stigma is fading, and there has been renewed interest in their therapeutic potential.

Numerous studies have shown that psychedelics used with psychotherapy can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression. Similar effects are seen with recreational or ceremonial use.

The evidence base for treatment of pain is small but growing. One source of research is the Psychedelics and Health Research Initiative at the University of California San Diego. (The team includes VS Ramachandran.) This group recently published a review article on the use of psychedelics for chronic pain.

The review cites a small number of studies showing that psychedelics can have positive effects on various kinds of pain, including cluster headaches, phantom limb pain and neuropathic pain. For example, LSD worked better than an opiod for reducing cancer pain in the short term.

I didn't see any studies describing longer-term effects, but there is a decent amount of research showing that psychedelics can create long-term changes in psychology, including the kinds of changes you'd probably want to make to get over chronic pain.

The problem with chronic pain: maladaptive neural “habits”

People with chronic pain have abnormal patterns of brain activity in areas known to be involved in pain perception. Research by Vania Apkarian and colleagues shows that this abnormal activity involves high levels of functional connectivity in certain parts of the limbic system. Apkarian considers these patterns to be in the nature of a bad “habit” that is hard to break.

This idea helps explain why chronic pain can persist over long periods of time, even after a painful body part heals from injury. Sensory input from the painful area may change, but pain remains the same, because the brain areas that process the sensory information are stuck in a maladaptive groove.

Psychedelics can change neural habits

Psychedelics create profound changes in the brain’s functional connectivity, probably because of its effects on serotonin, a neural transmitter. According to Castellanos 2020:

Several imaging studies have demonstrated that psychedelics alter established patterns of connectivity within the brain by reducing the stability and integrity of established brain networks and by increasing the global integration between established brain networks.

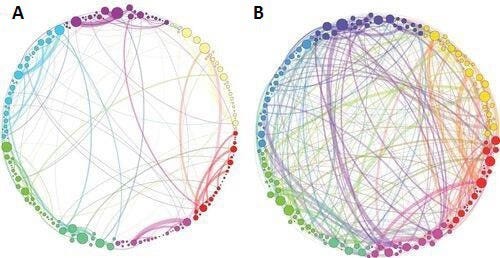

Here’s a diagram illustrating this: Circle A depicts normal functional connectivity between different brain regions, and Circle B shows a brain on psilocybin.

The authors conclude that these changes may explain why psychedelics can help with pain:

Given the accumulating evidence of altered brain functional connectivity in chronic pain states, the ability of psychedelics to disrupt established brain connection patterns is perhaps the most intriguing potential analgesic mechanism for psychedelics.

That's interesting, but are these disruptions merely temporary?

Any drug can create temporary changes in psychological state. But psychedelics might be able to change psychological traits, which persist over time. For example, psychedelics seem to cause lasting changes in openness to experience, which is one of the “Big Five” personality traits. Openness to experience is roughly synonymous with open-mindedness, and describes an attraction to new ideas and experiences. Psychedelics may also lead to changes in two other big five traits, reducing both neuroticism and introversion.

Ly 2018 argues that psychedelics promote functional and structural plasticity of the brain by creating new neural connections:

psychedelic compounds such as LSD, DMT, and DOI increase dendritic arbor complexity, promote dendritic spine growth, and stimulate synapse formation. These cellular effects are similar to those produced by the fast-acting antidepressant ketamine and highlight the potential of psychedelics for treating depression and related disorders.

Davis 2020 concludes that changes in depression and anxiety brought about by psychedelics are mediated by increases in “psychological flexibility”, which is defined as the ability to adapt to stressors and act in accordance with values. The degree of psychological flexibility created by a psychedelic experience may depend on its intensity, including whether there are feelings of awe, mystical realization, or ego dissolution.

Psychedelics and predictive coding

Karl Friston, one of the main proponents of the predictive coding model for perception, has an article here explaining why psychedelics are a promising treatment for anxiety and depression. It articulates the REBUS model, which stands for Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics.

The theory is basically this: conditions like anxiety, depression, and chronic pain are characterized by pessimistic “beliefs” about emotional or physical safety, and these beliefs negatively affect perception and behavior. These beliefs were probably adaptive at one time, but became resistant to change in the face of new evidence. Psychedelics create the flexibility that is necessary for these beliefs to be updated. Predictive coding provides an elegant explanation for exactly how this happens.

Following is some extensive quoting from the paper explaining some of the details behind this theory. There is a lot of jargon here, and to understand it, you might want to read this previous article I wrote about predictive coding.

The basic problem with anxiety and depression (and chronic pain):

We propose that many, if not most, psychopathologies develop via the gradual (or rapid—in the case of acute trauma) entrenchment of pathologic thoughts and behaviors, plus aberrant beliefs held at a high level, e.g., in the form of negative self-perception and/or fearful, pessimistic, and sometimes paranoid outlooks.

Note that these “beliefs” are not necessarily conscious. Think about the “beliefs” you might have about your physical safety after being violently assaulted, or your emotional safety after the death of a loved one, or the safety of your neck after a whiplash accident. You might consciously believe you are safe, but unconscious parts of you are on the defensive.

Under the predictive coding model, these beliefs are called “priors.” They generate predictions, which are encoded in top-down neural signals that alter the processing of bottom-up sensory information. This top-down modulation means that perception is biased toward expectation. This isn how illusions work - you see what you predict is there. The degree of the bias depends on the “precision” or “weighting” of the prediction, which basically means the confidence of the prediction:

We also propose that these pathologic beliefs are ascribed excessive precision, weight, or influence in many psychiatric disorders. …

Psychedelics work to relax the precision weighting of pathologically overweighted priors underpinning various expressions of mental illness. We propose that this process entails an increased sensitization of high-level priors to bottom-up signaling (stemming from intrinsic sources), and that this heightened sensitivity enables the potential revision and deweighting of overweighted priors.

What this basically means is that psychedelics open your mind to new evidence suggesting maybe things aren’t so bad. How does this actually happen?

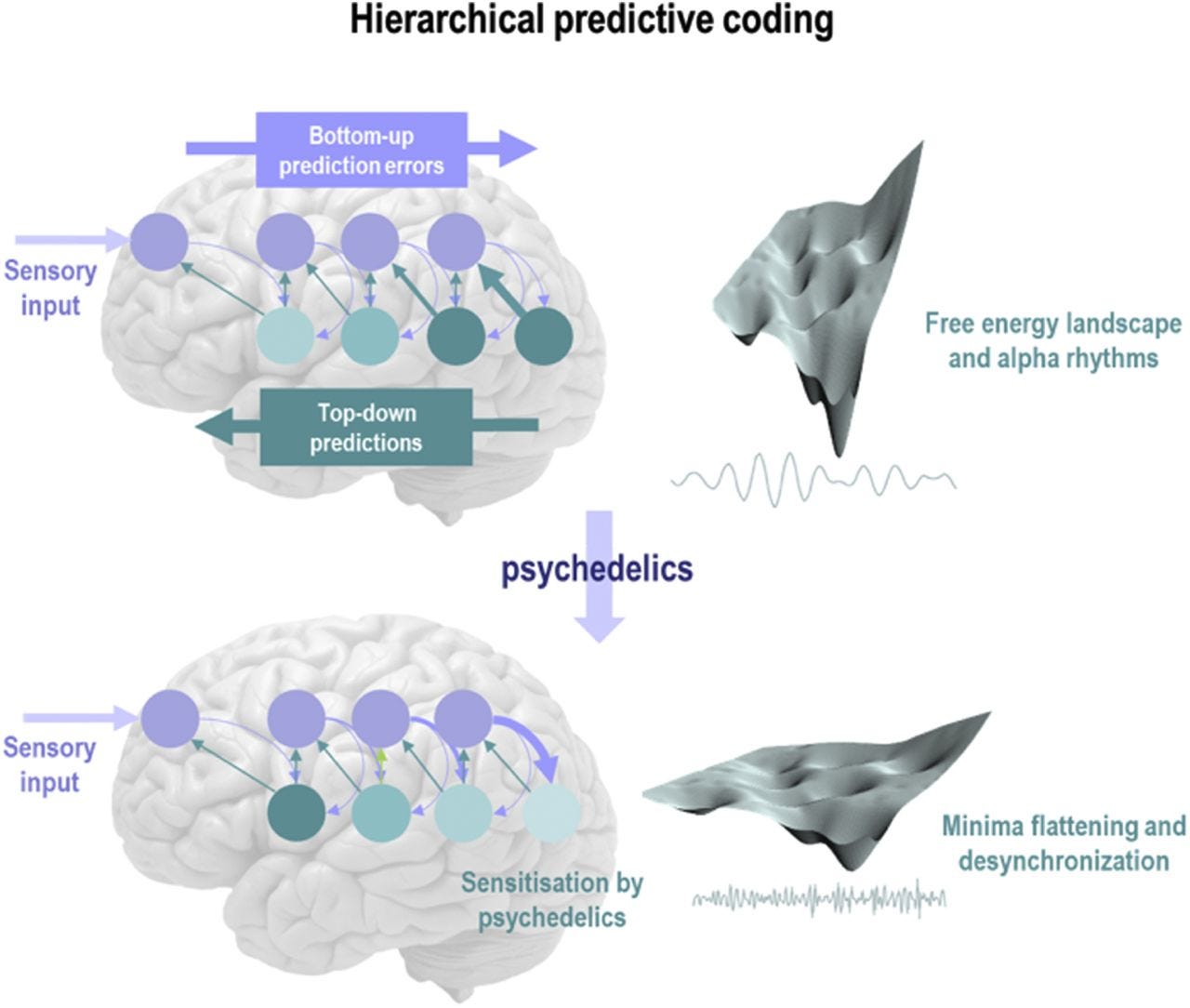

Here is a diagram, with some quotes below, explaining the basic neural mechanisms of the predictive coding model, and the effects of psychedelics on its operation:

Under normal conditions, predictive coding works like this:

Sensory input is compared with descending predictions. The ensuing prediction error (blue circles; e.g., neuronal populations of superficial pyramidal cells) is then passed forward into hierarchies, to update expectations at higher levels (blue arrows). …

The recurrent neuronal message passing (i.e., neuronal dynamics) tries to minimize the amplitude of prediction errors at each and every level of the hierarchy, thereby furnishing the best explanation for sensory input at multiple levels of hierarchal abstraction. …

Crucially, this process depends upon the precision (ascribed importance or salience) afforded to the ascending prediction errors (surprise) and the precision (felt confidence) of posterior beliefs. …

Psychedelics affect the operate of this system in the following way:

Psychedelics act preferentially via stimulating 5-HT2ARs on deep pyramidal cells, which are thought to encode posterior expectations, priors, or beliefs. The resulting disinhibition or sensitization of these units lightens to precision of higher-level expectations so that (by implication of the model) they are more sensitive to ascending prediction errors (surprise/ascending information), as indicated by the thick blue arrow in the lower panel.

Ascending prediction errors from lower levels of the system (that are ordinarily unable to update beliefs due to the top-down suppressive influence of heavily-weighted priors) can find freer register in conscious experience, by reaching and impressing on higher levels of the hierarchy

Psychedelics seem to have greater effect on higher levels of the neural hierarchy:

this relaxation process is felt most profoundly when it occurs at the highest or deepest level of the brain’s functional architecture, i.e., the levels that instantiate particularly high-level models such as those related to selfhood, identity, or ego

This fits in well with the evidence discussed above, showing that psychedelics create more psychological flexibility when they involve an experience of mysticism or ego dissolution. More on high-level beliefs:

an important example of a high-level prior is the belief that one has a particular personality and set of characteristics and views. This (umbrella) belief is commensurate with the narrative self or ego. It is proposed in this work that dissolving high-level priors has implications for the functioning of the rest of the hierarchy—and indeed the integrity of the hierarchy itself.

In other words, psychedelics might affect the most basic and fundamental stories we tell about ourselves, our most basic self-image, and these changes have profound top-down effects. They “constrain” the information that can be processed at lower levels:

It follows from hierarchical predictive coding that precise high-level priors or beliefs ordinarily have an important constraining influence on the rest of the hierarchy, canalizing lower components and inhibiting their expression and influence.

So psychedelics create freedom of information flow. Which can be good, but it can also be bad. (Think of social media.) Too much freedom can lead to uncertainty, chaos, and anxiety:

Thus, rather than the mind and brain being constrained to a small number of gravitationally dominant attractors (i.e., states or sequence of states), the mind and brain spontaneously transition between states with greater freedom—and in a less predictable way. These altered dynamics may be felt as an enriched or broadened global state of consciousness—and a sense of the mind opening up (Atasoy et al., 2017). Equally, however, they may be felt as aversive and disconcerting.

This is why some trips are bad, and some people go a bit crazy after psychedelics. Ego dissolution is a risky thing. I look forward to more research.

Here’s an article from Scott Alexander with some skepticism. And another from Scott with analysis of the Friston paper.

Thanks to Zach Haigney for recommending this as a subject for the newsletter and pointing to some of the key studies. Check out his blog at The Trip Report.