Changing Beliefs to Treat Back Pain

A New RCT Showed Dramatic Results for Pain Reprocessing Therapy

A new study found that Pain Reprocessing Therapy (PRT), a psychological treatment for chronic low back pain, worked very well. Here’s the headline:

Two thirds of the treatment group were virtually pain free after one month of treatment. These improvements were mostly retained one year later.

This is an unusually good result for low back pain treatment, and the study appears to be well done. So I decided to take a closer look, and to ask a bunch of my smart researcher friends what they thought. Here's what I found out.

Study details

The study was a preregistered randomized clinical trial published in JAMA Psychiatry, a respected journal. It was done at the University of Boulder and lead by Yoni Ashar, a psychiatrist, Tor Wager, a neuroscientist, and Alan Gordon, a psychotherapist who developed PRT.

It recruited 150 adults with chronic low back pain that was likely nociplastic in nature - that is, driven mostly by excessive nervous system sensitivity, as opposed to peripheral tissue damage or neuropathy. The average intensity level of the pain was low/moderate (4 on a scale of 1-10), and the average duration was 10 years.

The 150 participants were randomly divided into three groups that received one of three different treatments: (1) PRT, given in 8 one-hour sessions by expert providers twice a week for a month; (2) "open label" placebo injection; or (3) the usual care that they were already receiving when the study began.

Patients reported their pain levels after one month and then various intervals up to one year. Other outcomes were beliefs about pain, and fMRI results showing brain activity during movements designed to evoke pain.

The results

After the one-month treatment program ended, two thirds of the patients in the PRT group saw their pain reduced from an average of about 4/10 to 1/10 or 0/10. Only 20% of the placebo group and 10% of the usual care group had similar improvements. One year later, these group differences were slightly smaller but largely intact.

The fMRI results showed that the PRT group had different patterns of brain activity in response to painful movements compared to the placebo and usual care groups. This might indicate that they were experiencing less negative emotion in processing nociceptive signals.

The PRT group had less fear of movement after treatment than the other groups, and this may explain why they had less pain. (Also, less pain may explain why they had less fear of movement, so there may have been a positive feedback loop here.)

After looking at these results, I was surprised to see such large effect sizes for pain reduction, as this is unusual for any kind of low back pain treatment, including psychological interventions. I asked several back pain researchers what they thought and they all had the same reaction.

This raises the question: how did PRT achieve large effect sizes using treatments that appear similar to methods that typically produce small effect sizes? Are there any important differences between the methods? To answer that we need some more detail on what happens with PRT.

So what exactly is PRT?

PRT was developed by the psychotherapist Alan Gordon. The main goal is to reduce excess nervous system sensitivity to threatening sensory input. Importantly, it is not recommended for pain that is driven more by peripheral pathologies like neuropathy or tissue damage.

PRT seeks to reduce nervous system sensitivity by changing beliefs about pain. In essence, PRT teaches the patient to think of pain as "a brain-generated false alarm." Why is this a good idea? Here is a detailed explanation from the study:

In approximately 85% of cases [of chronic back pain], definitive peripheral causes cannot be identified, and central nervous system processes are thought to maintain pain ...

In constructionist and active inference models, pain is a prediction about bodily harm, shaped by sensory input and context-based predictions. Fearful appraisals of tissue damage can cause innocuous somatosensory input to be interpreted and experienced as painful. Such constructed perceptions can become self-reinforcing: threat appraisals enhance pain, which is in turn threatening, creat- ing positive feedback loops that maintain pain after initial injuries have healed.

As pain becomes chronic, it is increasingly associated with activity in the affective and motivational systems tied to avoidance and less closely tied to systems encoding nociceptive input. …

We developed pain reprocessing therapy (PRT) based on this understanding of primary chronic pain ... PRT emphasizes that the brain actively constructs primary chronic pain in the absence of tissue damage and that reappraising the causes and threat value of pain can reduce or eliminate it. …

It presents pain as a reversible, brain-generated phenomenon not indicative of peripheral pathology, consistent with active inference and constructionist accounts of interoception and pain.

These ideas will be familiar to readers of this blog and others who have been studying pain science. For example, there is strong evidence developed over many decades showing that:

Chronic pain does not correlate well with tissue damage. In many cases the more important driver of pain is excess nervous system sensitivity.

Chronic pain is associated with negative emotional states like fear, anxiety, and depression. Recovery from chronic pain is associated with positive mind states like optimism and self-efficacy.

Expectations can affect pain through placebo and nocebo effects. This is well-explained by the predictive processing model for cognition, which notes that we often perceive in accordance with expectancies or predictions.

The transition from acute to chronic pain involves brain changes, whereby emotional centers become more involved in pain processing.

So how does PRT get patients to reconceptualize the cause of their pain, reduce negative emotional states, and expect improvement? The study lists four major strategies:

Educating the client that their pain derives from excess nervous system sensitivity, and that such sensitivity is reversible.

Helping the client reappraise the meaning of painful sensations during exposure to feared postures or movements.

Techniques to reduce fears or other emotional threats.

Techniques to increase positive emotions.

(You can read more detail on the specifics here, at a website for PRT, and in the supplemental materials for the study.)

In my opinion, the strategies listed above are all great, backed by solid evidence and reasoning. But they they are not unique to PRT. I have advocated all of them at one time or another in my writing. My friend Greg Lehman, who teaches therapists how to incorporate pain science into their practice, said this is almost exactly how he tries to practice.

There are many different treatment models for chronic pain that recommend similar psychological techniques, such as: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Explain Pain, Therapeutic Neuroscience Education, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, Graded Motor Imagery, Cognitive Functional Therapy, exposure therapy and others. Further, when physical therapy is provided through a biopsychosocial lens, it will incorporate some and often all of these psychological techniques.

Most of the above methods have been tested by RCTs to examine their effect on pain. The results are of course heterogenous, but systematic reviews and meta analyses synthesizing the best evidence discern a pattern: psychologically oriented treatments for chronic pain tend to have small effect sizes on pain, not the dramatic effects seen with PRT. (This point is made several times in the PRT study.)

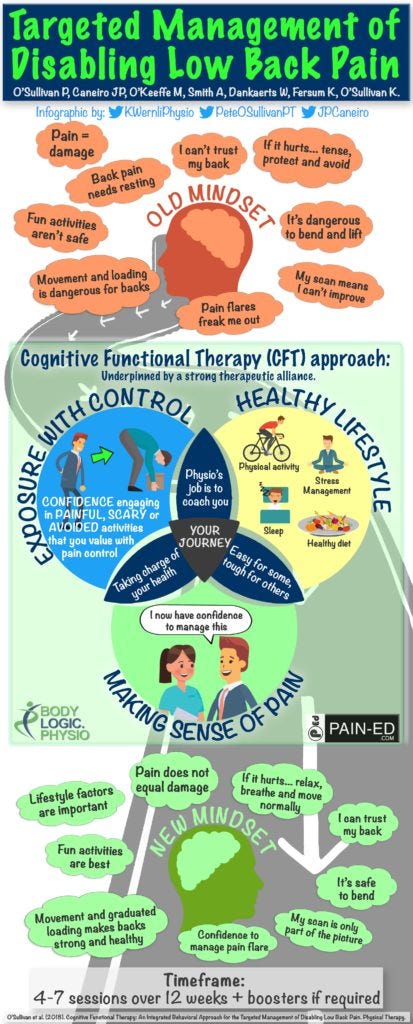

For example, CFT, which is in my opinion an excellent treatment model, has been found to be effective in changing mindset about pain and reducing disability, but not much better than core exercise in reducing pain. Here’s an infographic illustrating its main components, some of which appear quite similar to PRT:

According to the graphic, the main goal of CFT is changing patient mindset from negative to positive through education about pain, mindful movement practices, addressing fears, and developing optimism and self-efficacy. This excellent framework sounds very similar to PRT. (By the way, click here for a podcast interview with Kieran O’Sullivan one of the developers of CFT, and here for more information on CFT.)

So how is PRT different? Ashar and co-authors argue that PRT may be more optimistic in its client education concerning the ability to reverse sensitivity and eliminate pain. By contrast, other methods may focus less on pain reduction, and more on pain acceptance, management, and disability. This more “realistic” approach might reduce the optimism and positive expectancy needed for dramatic results.

Perhaps this is a valid distinction, and it raises some interesting questions that are frequently asked by therapists in the pain science community: if we tell clients that they can eliminate their pain by changing their brain, does this potentially blame them for their pain if they fail? Or suggest that pain is all their head and not real? Or give them false hope that leads to disappointment? These are all important considerations, often without easy answers, and of course should be addressed on an individual basis.

My takeaway

I see the results in this study as encouraging but in need of replication given the existing evidence base about similar treatments. Comments about the study are welcome below.

I am also excited to see this study get attention on social media from several scientific authorities who don’t normally take an interest in back pain. Hopefully this publicity will lead to more research and widespread understanding about back pain. I look forward to it!

Great article, Todd! In my experience, the main difference between prt and some of the other treatments you listed is the form of exposure. Combining mindfulness, safety reappraisal and positive affect induction maximizes the chance of giving the patient a corrective experience. Once the patient experiences the position or activity with no pain, it often eradicated the illusion that the pain is an accurate reflection of tissue damage. And allows the patient to over the fear of the pain. Here’s an example of the technique in action:

https://m.soundcloud.com/alantgordon/ep4-v8-mixdown-0001

Alan

Hello Todd,

Thanks for writing about this study and engaging with the ideas! I'm a former chronic pain patient and I made a film that explores this new treatment approach through filming with one of the study's authors, Dr. Howard Schubiner, and a few of his patients. He was in charge of examining and "re-diagnosing" the people in this PRT study, and you can see more about how he does it in our film, This Might Hurt.

A key part of the process is ruling out a tissue damage process (herniated discs, pinched nerves) which so many patients have become so scared of — that their backs are damaged. And then educating people that in the absence of tissue damage, brain-induced pain is 100% reversible. Then learning so many things held in common by practitioners of CFT, MBSR, or PRT etc., which can have a more powerful effect (60% in this study who were assigned to PRT became nearly pain-free). Some of the specific techniques used in PRT like somatic tracking are really helpful in reducing fear of pain, and wearing away the belief that the body is damaged, and that pain is always a sign of damage.

The group of practitioners who authored this study is having a large conference and training in two weeks. They train a lot of physical therapists to do this work. Might be worth checking out! https://ppdassociation.org/