I’ve written before about research examining associations between back pain and posture. There are few associations to be found, which calls into question the common belief that we should spend a lot of time worrying about alleged postural dysfunctions like forward head posture, slumping, or anterior pelvic tilt.

But what about scoliosis? Here the research is more mixed, and there is some evidence that lateral curvature of the spine is associated with back pain, especially in moderate or extreme cases. This post summarizes some basic information and relevant research. It will be mostly relevant to people who have mild scoliosis.

Some degree of asymmetry is normal

The human body is inherently asymmetrical in certain respects. The heart is on the left, and the liver is on the right. To compensate for these differences, the right lung is slightly bigger than the left, and the right side of the diaphragm is slightly higher. So every breath you take, the whole rib cage and related musculature is working slightly differently on the left compared to the right.

It's also normal for humans to have a dominant arm and a dominant leg, and this necessarily leads to structural differences from side to side. Even in parts of the body which don't really have any reason to be different, such as two sides of the same face, you can spot obvious differences if you look closely.

Here's a good example from a vertebra:

Check out how that spinous process curves right. You can find similar asymmetries in every other aspect of this picture, and indeed in every other part of the body’s structure.

Many of my clients have noticed these kinds of side to side differences in the spine, and worry that they have scoliosis. In most cases, the differences are small and completely normal. Scoliosis involves relatively large side to side asymmetries, and affects only 3% of the population. So, how much curvature of the spine do we need to see before we call it scoliosis?

What counts as scoliosis?

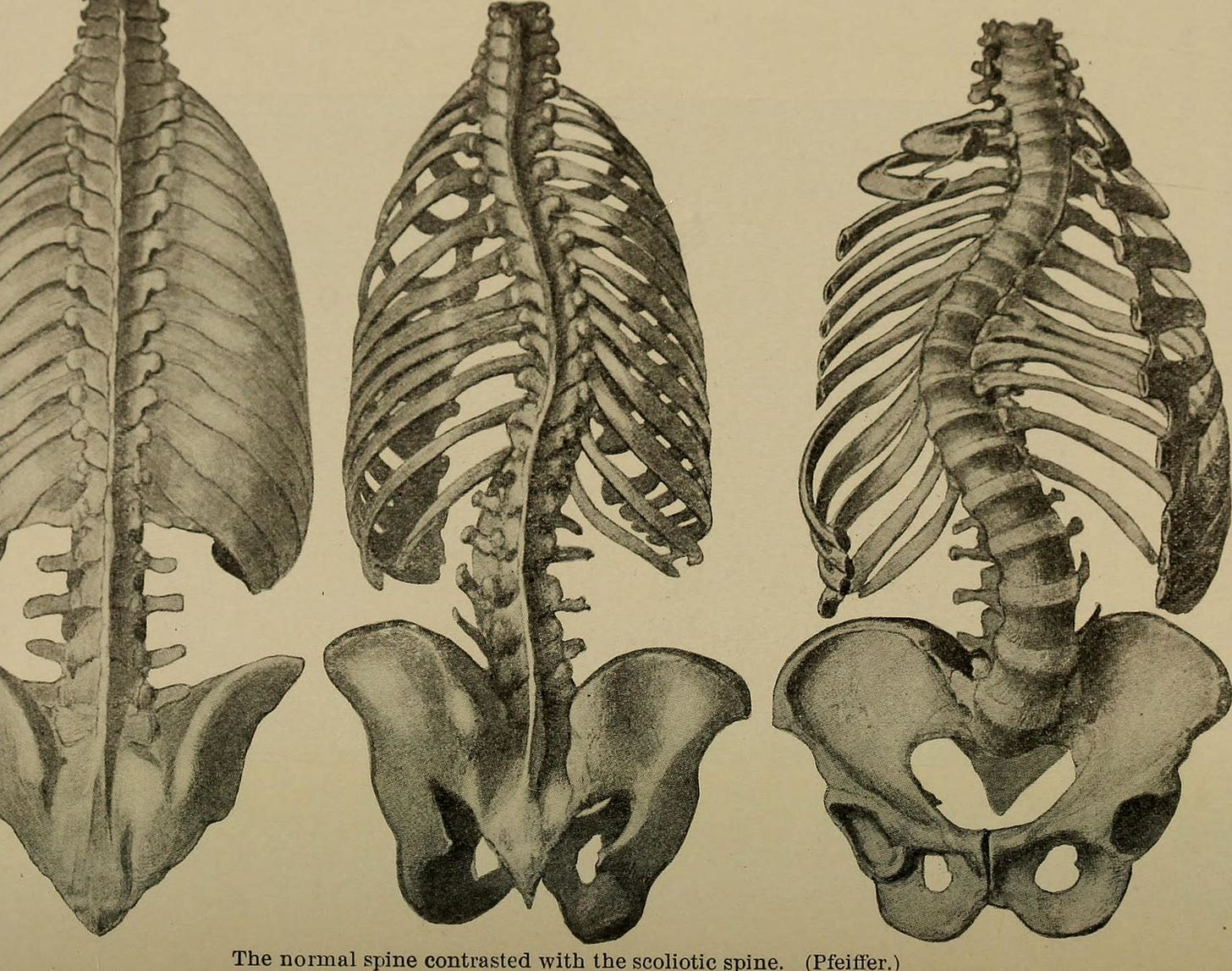

The key variable is the Cobb angle, which is the maximum side to side angle between vertebrae in a particular region. Below is a picture of spine showing Cobb angles of 42° on top, 89° in the middle, and 47° on the bottom.

Cobb angles between 10° and 30° are classified as mild scoliosis, 30-45 is moderate, and anything over 45 is severe. Curves between 0-10° are common and not considered to be scoliosis.

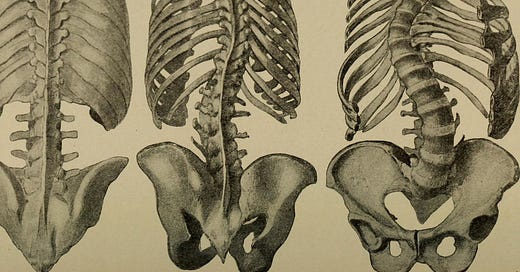

Below are some pictures and related x-rays showing what moderate scoliosis looks like. Each of the people below have 40° Cobb angles in their back.

It is important to note that the curvatures seen in the above pictures are caused to a large extent by the shape of skeleton, not just asymmetries in the soft tissues.

In other words, if you somehow equalized the pull of the muscles and fascia around the spine, it would remain curved. If the spine was straightened, the joints would not be in neutral positions.

These are important points, because once you are an adult, the shape of your skeleton will not change to any significant degree.

How does scoliosis develop and what causes it?

Scoliosis usually develops between the ages of 10 and 20, and is far more common in women than men. The majority of cases are labeled idiopathic, meaning the cause is unknown. A minority are congenital, or caused by rare neuromuscular diseases.

Scoliosis is usually identified in adolescence, and progresses until adulthood, at which point the degree of curvature becomes more stable. Progression is more likely when the curves are larger.1 There is weak evidence that after skeletal maturity, curves progress at the rate of about 1° per year.2

Scoliosis and health

There are three major health concerns related to scoliosis: pulmonary function, back pain, and psychological issues related to self-image. Although the initial research on these topics painted a fairly negative picture, recent updates are more encouraging.

A good deal of the relevant evidence derives from what are called the Iowa studies, which followed a large group of adults with untreated idiopathic scoliosis over decades.

The most recent findings come from a 50-year follow up study, which included 117 people with severe scoliosis. The average Cobb angles of the participants were quite high: 80° thoracic, 90° thoracolumbar, and 50° lumbar. The health of these people was compared to a control group with normal spines. The general finding was that the scoliosis group was doing pretty well, and not that different from the control group.3 Here are the specifics:

Back pain: 61% of the scoliosis group reported back pain, and this figure was only 35% in the control group. When the intensity and duration of pain was considered, the differences between the groups were smaller (total score of 7 compared to 6).

Pulmonary function: 22% of the people in the scoliosis group had shortness of breath, compared to only 15% of the control group.

Mortality: 2% lower in the scoliosis group compared to the control group.

Disability and depression: slightly more in the scoliosis group.

Many other studies have found that people with scoliosis are slightly more likely to have back pain.456 The evidence is mixed on whether higher levels of curve correlate with higher levels of pain.78 Most of these studies involve adolescents.

One might assume that scoliosis creates pain because of structural asymmetries in the spine, but the cause for the association remains unclear. In fact, it's been recently found that adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis have lower levels of pain modulation.9

Scoliosis and physical function

Some people with scoliosis may believe that it limits their ability to safely compete in sport, or to engage in strenuous physical activity. I'm not aware of any research to specifically test this idea, but it’s easy to think of examples that call it into question. In my own practice, I have treated elite golfers, dancers, and gymnasts with moderate scoliosis.

One of the greatest athlete of all time, Usain, Bolt, has a 40° of lateral curvature in his back.

The powerlifter Lamar Gant had a huge curve in his spine, and managed to break the world record in the deadlift, becoming the first person to lift more than five times his own bodyweight.

Everyone has physical limitations, and they will meet them sooner or later if they put enough stress on their body. There are hundreds or maybe thousands of different biological factors that determine these limits. The presence of scoliosis may sometimes be a relevant factor, but just one of many, and often insignificant.

Exercise and scoliosis

Treatment for scoliosis is usually done in adolescence to prevent progression in cases were curvatures are progressing from moderate to severe. Treatment may involve bracing, surgery, and specific exercises. The efficacy of these different methods is a big topic that I won't be address in any detail. But here are some general thoughts about exercise.

The evidence suggesting that specific exercises may be helpful for scoliosis is generally of low quality.10 Based on my general understanding of how the bodily tissues respond to exercise, I would be surprised if specific exercises could make significant changes in spinal curvature. To illustrate, imagine that you tried to straighten the spine by stretching the tissues on the short side of a curvature, and strengthening them on the long side. Stretching can increase range of motion, but this is probably caused by increasing tolerance of the nervous system to stretch, rather than adding physical length to the muscles.11 Similarly, strengthening the muscles on the long side of the curvature might make them more capable of shortening, but they would not get physically shorter.

In any event, even if you succeeded in changing the structure of the soft tissues on either side of the spine, the structure of the bones would remain curved. Thus, the changes caused by exercises focused on asymmetrical stretching and strengthening would probably be more functional than structural.

This is true about exercise in general. Aside from adding muscle or subtracting fat, exercise is far more likely to change your function than your structure. Therefore, when you are deciding how to exercise, you should put most of your focus on what you want to be able to do, and not how you want to look.

If you want your back to have good mobility, being able to move into flexion, extension, rotation, and side-bending, then work to improve your mobility, and spend more time on your weaknesses. If you want your back to be strong and stable, work on functional strength and stability. If it hurts to do something, try doing that thing with less frequency and intensity, and build up your capacity slowly. These general common sense rules apply to people with and without scoliosis.

There are probably some specific individual considerations that apply to people with large spinal curves, and they should consult experts who understand these limitations. But as noted before, everyone has physical limitations, and scoliosis is just one of them. My reading of research is that it matters, but not as much as most people tend to think.

References

Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, Peterson KK, Spoonamore MJ, Ponseti IV. Health and function of patients with untreated idiopathic scoliosis: a 50-year natural history study. JAMA. 2003 Feb 5;289(5):559-67. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.559. PMID: 12578488.

Agabegi SS, Kazemi N, Sturm PF, Mehlman CT. Natural History of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis in Skeletally Mature Patients: A Critical Review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015 Dec;23(12):714-23. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00037. Epub 2015 Oct 28. PMID: 26510624.

Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, Peterson KK, Spoonamore MJ, Ponseti IV. Health and function of patients with untreated idiopathic scoliosis: a 50-year natural history study. JAMA. 2003 Feb 5;289(5):559-67. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.559. PMID: 12578488.

Mayo NE, Goldberg MS, Poitras B, Scott S, Hanley J: The Ste-Justine idiopathic scoliosis cohort study. Part III: Back pain. Spine. 1994, 19: 1573-1581.

Ramirez N, Johnston CE, Browne RH. The prevalence of back pain in children who have idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:364–8

Sato T, Hirano T, Ito T, Morita O, Kikuchi R, Endo N, et al. Back pain in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: epidemiological study for 43,630 pupils in Niigata City. Japan Eur Spine J. 2011;20:274–9.

Théroux J, Le May S, Hebert JJ, Labelle H. Back Pain Prevalence Is Associated With Curve-type and Severity in Adolescents With Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Cross-sectional Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017 Aug 1;42(15):E914-E919. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001986. PMID: 27870807.

Asher, M.A., Burton, D.C. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: natural history and long term treatment effects. Scoliosis 1, 2 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-7161-1-2

Teles AR, Ocay DD, Bin Shebreen A, Tice A, Saran N, Ouellet JA, Ferland CE. Evidence of impaired pain modulation in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis and chronic back pain. Spine J. 2019 Apr;19(4):677-686. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.10.009. Epub 2018 Oct 19. PMID: 30343045.

Thompson, J., Williamson, E., Williams, M., Heine, P., & Lamb, S. (2018). Effectiveness of scoliosis-specific exercises for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis compared with other non-surgical interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy, 105(2), 214–234.

Weppler et al. (2010). Increasing Muscle Extensibility: A Matter of Increasing Length or Modifying Sensation? Physical Therapy. 90 (3): 438–49.

Loved this! Thanks Todd

I may have built up this false belief over time that if my body isn't perfectly balanced and symmetrical then it will cause issues for me down the line.

Much better to think about how to work within the variances in each of our bodies.

This speaks to the mystery of back pain which is covered a lot in the TMS John Sarno mind-body dysfunction world where I look for information to treat chronic pain after Covid. Essentially their belief is a high majority of back surgeries are unnecessary as the problem stems from the brain and not the actual curvature or degeneration of the spine. Your study seem to support it as well given that the groups followed in the study didn't differ that much from the control group. Do you also believe that back pain results from physiological condition rather than anything in the back