Note: This is the third chapter of my serialized book Healthy Movements for Human Animals. You can find an archive of previous chapters here.

In the previous chapter, we examined how human movement can be understood in terms of four distinct functional environments that shaped our evolution: Ground World, Tree World, Bipedal World, and Tool World. Ground World is the foundation, and consists of movements we perform in close proximity to the earth, such as rolling, crawling and squatting. These movements build the mobility and postural control that supports the movements we do in standing.

Hunter-gatherers and children spend hours each day in Ground World, skillfully transitioning between a variety of different postures while working or playing. This develops what I call “ground flow”, which means moving with agility near the ground.

Most modern adults have lost their ground flow, and rolling is the best place to start in trying to recover it. It’s the most basic movement in Ground World, and literally the most grounded you can be while still moving. It’s also the easiest way to make smooth transitions between ground-based positions, connecting lying, sitting, and crawling. More importantly, rolling develops the fundamental postural skill of "righting" - controlling your body as it changes orientation to gravity. This skill forms the foundation for balance and coordination in more complex movements.

This chapter reviews the evolutionary and developmental history of rolling, how it appears in natural settings and in sports, and the way it’s used in athletic training and rehabilitation. Then it provides a series of videos demonstrating rolling exercises you can practice on your own, as a way to improve basic postural skills and body awareness.

The function of rolling

Rolling serves two basic functions: changing position while lying down (e.g. from back to front) or transitioning from lying to sitting. In the modern world, we associate these movements with leisure, and therefore consider them to be of little functional importance. But in the natural world, rolling plays a key role in at least three contexts that involve physical emergencies: getting up quickly to flee danger, absorbing the impact of a fall, and maneuvering during ground-based combat. Let's consider them in turn:

Fleeing. Imagine lying on your back and then noticing the approach of a dangerous predator. You need to roll quickly to a quadruped position, similar to a sprinter's starting position, before rising and running.

Falling. If you fall while running, you will land much easier if you roll through the fall. Rolling comes up frequently in sports when athletes expect to hit the ground with force, such as parkour, judo, or soccer goalkeeping. Sometimes the rolling pattern that allows a graceful fall is the mirror image of rising from the ground to run. Both scenarios have something in common - a quick transition between vertical and horizontal posture under chaotic conditions.

Ground combat. Consider the movements of dogs during play fighting - a fundamental move involves rolling from a defensive position on their back to an offensive stance on their front. Jiu-jitsu practitioners and wrestlers are constantly making the same transitions. In fact, they often call their practice “rolling.”

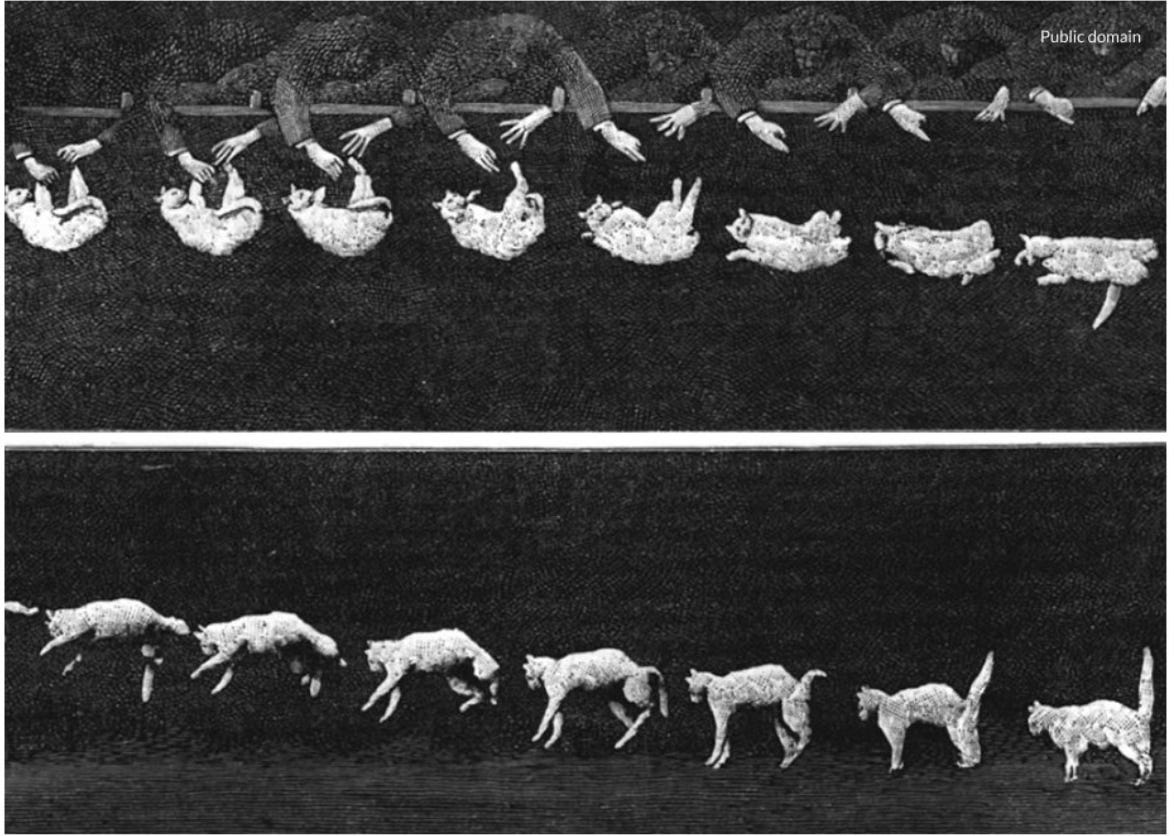

The above movements happen only rarely, but they directly impact survival, so natural selection placed strong pressure on our ancestors to adapt to them. The key skill common to each is controlling the body as it makes large and dynamic changes in its orientation to gravity. This is called "righting," which simply means moving from the “wrong” position to the right one. It is dramatically shown by a cat's amazing ability to "right" itself in the air during a fall through rolling.

Righting presents a unique postural challenge. In just seconds, you go from facing up, to facing sideways, to facing down. Gravity keeps changing its direction of pull, so you need to constantly change the patterns of muscular activity that are providing postural stability. Vestibular organs in your inner ear sense each change in head tilt, then communicate directly with the spinal cord to adjust muscle tone throughout your body. Front muscles (anterior chain) work when you are face up, side muscles (lateral chain) when you're on your side, and back muscles (posterior chain) when you're face-down.

These same righting processes control posture in upright standing, but in a more subtle way. Even as we stand still, our center of mass is always “falling” a bit to one side, moving back to the center, and then falling again, so that we are always oscillating just a few millimeters around a center point. When your head tilts in one direction (either forward, back, left, or right), chains of muscle on the opposite side automatically engage to bring the body back to center.

Rolling activates these same righting mechanisms, except with far greater amplitude and speed. This may be why rolling precedes upright postural balance in the developmental sequence.

Rolling and infant development

When infants begin rolling around 4-6 months, they're learning to control and refine these patterns of postural control. This involves two distinct stages. At 4-5 months, infants start “log rolling”, which means the entire body moves as one unit - the head, shoulders, trunk and pelvis all turn together.