Four Worlds of Movement

Chapter Two of Healthy Movements for Human Animals

Note: This is the second chapter of my serialized book "Healthy Movements for Human Animals." You can read the introductory chapter here, and chapter one here.

In the previous chapter, we looked at the History of Human Movement, following the 400-million-year evolution of our ancestors from quadrupeds walking on all fours, to primates climbing trees, and finally to humans walking upright and manipulating objects. Each stage of evolution developed physical capacities that we can still access today.

In this chapter, we’ll use that history as a lens to categorize the various ways we can move. We’ll identify four distinct environments or “worlds” in which each of our primal movement abilities evolved, and which humans living in natural settings continue to visit:

Ground World: Movements performed close to the ground, which are built on the foundation of our quadrupedal heritage (sitting, squatting, crawling, rolling.)

Tree World: Movements that involve using strength to move our bodyweight up and down in vertical space (reaching, hanging, climbing).

Bipedal World: Locomotive movements on two feet at a variety of speeds and directions (walking, running, jumping and agility).

Tool World: Movements that involve manipulating objects (lifting, carrying and throwing).

This environmental perspective is useful for several reasons. First, it provides an easy way to simplify the complex task of categorizing human movements, which are incredibly diverse and varied. Second, it helps us identify the essential components of a healthy movement “diet.” Third, it suggests ways to progress or regress exercise to meet individual needs. Fourth, it makes us more aware of opportunities for healthy movement in our daily environment.

In this chapter, we'll explore how hunter-gatherers and children naturally move within each world, examining what physical challenges they encounter, and what fitness qualities they develop as a result. We'll also look at how modern exercise methods attempt to recreate similar challenges. The goal is not to replicate ancestral movement patterns, but rather to establish reference points that can guide our choices about how to exercise.

1. Ground World

“Ground World” simply means the world of movements that humans naturally perform when they are on the ground, such as squatting, sitting, crawling and rolling. Our facility with these movements derives from our quadrupedal heritage.

Hunter-gatherers spend many hours daily in Ground World - working with tools, digging for food, tending fires, preparing meals, or simply resting. They use a wide variety of stable postures for this activity, such as deep squats, kneeling, half-kneeling, cross-legged, side-sitting and long-leg sitting. Importantly, they frequently change between these postures to maintain comfort and perform ongoing work.1 These transitions may often involve crawling, as a way to reach something that is close by. Or rolling, as a way to move from lying down to standing - a useful skill when you’re resting in a savannah full of leopards and hyenas.

There's some common elements to all these ground-based movement patterns. One is that the body is in a flexed and compact posture, folded almost in half. The deep squat is the perfect example - the ankles, knees, hips and spine are near maximum flexion. Positions like this build mobility and functional strength in the legs.

Another key challenge in Ground World is making smooth transitions between all the different postural options. Let's call this ground flow. To see it in action, look at this video from author Frank Forencich, which shows some Hadza tribe members squatting around a fire, and constantly moving between different resting positions.

Can you move like this? You could when you were younger. Children practice their ground flow for hours each day when they play with toys on the floor, or dig in a sandbox. They constantly vary their position - squatting on the heels, kneeling, crawling, and moving frequently between sitting and standing. The floor is an ideal place for them to explore movement because there is a wide base of support, lots of feedback from the ground, and no danger of falling. These activities build the foundation for good function in standing.

Most adults in modern western societies have lost their ground flow, simply because they stopped spending time on the ground. This leads to major losses in lower body mobility and functional strength. These deficiencies are revealed during activities like gardening, assembling IKEA furniture, or sitting on the floor for an extended time. Many people feel stiff, creaky and uncomfortable in these activities.

There are many forms of modern exercise that focus on ground-based movements, including Feldenkrais, yoga, animal flow, and a wide variety of mobility drills, corrective exercises, and physical therapy movements. Notably, these exercises are usually intended to serve a rehabilitative or preparatory purpose. The rationale is that when someone has lost control over basic ranges of motion in the lower body or spine, the ground is the best place to reclaim them. This fits in well with the evolutionary and developmental perspective - proficiency in ground-based movements is the foundation for moving well on two feet.

In modern gyms, Ground World is poorly represented - it’s usually a small mat somewhere off in the corner. Fortunately, you don’t need a gym to start spending more time on the floor and doing the ground-based exercises in this book. Nor do you need to expend much energy. You just need to get off the couch.

2. Tree World

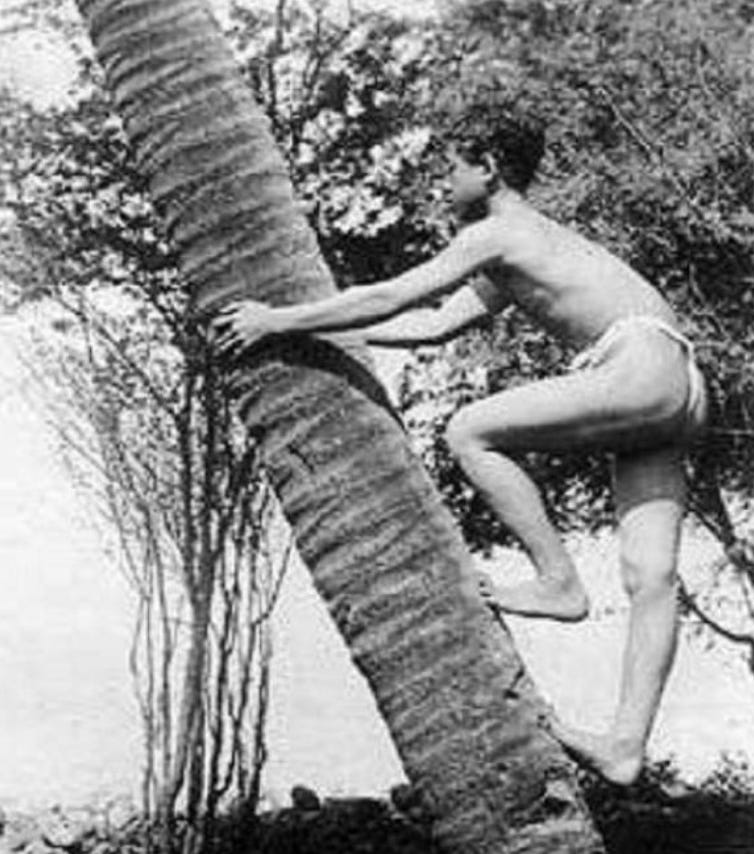

“Tree World” means the collection of movements that humans make while in trees, such as hanging, reaching and vertical climbing. Ethnographic studies show that most hunter-gatherers climb several times a week to get foods like honey and fruit.2

Children are natural climbers and will generally climb anything that can be climbed. They don't need to be taught or encouraged to develop proficiency. Even infants can grip and briefly hang from supports.

Although there are a huge variety of climbing techniques, they all share something in common - moving body weight up or down against the force of gravity, often with poor leverage, through compound joint movements of the arms and legs. These mostly involve:

Pulling with the arms in variable directions (e.g. pull-up or rowing motions)

Pressing with the arms in variable directions (e.g. dip or pushup motions)

Step-up, squat, or hip thrust/curling movements with the legs.

Isometrically abducting or adducting the arms for stability.

These movements require simultaneous activity of the upper and lower body, which means the core muscles must work hard to provide coordination and balance. We can therefore think of climbing as nature's full-body strength workout.

Another skill in climbing is lengthening the body vertically, to facilitate overhead reaching. This requires extending every joint from the toes to the finger tips and stabilizing the body in that extended position. In other words, climbing makes you better at getting long and strong. In this regard, it's the opposite of Ground World, which is about being short and mobile.

The forms of modern exercise that most closely mirror the kinds of movements we evolved to do in trees would be those which challenge us to control our body weight with full-body strength, especially in extended postures, such as gymnastics, yoga, calisthenics, rock-climbing and bodyweight strength exercise. It is notable that several of these methods are considered to be good ways to develop general athletic capacities that provide a solid foundation for a variety of sports.

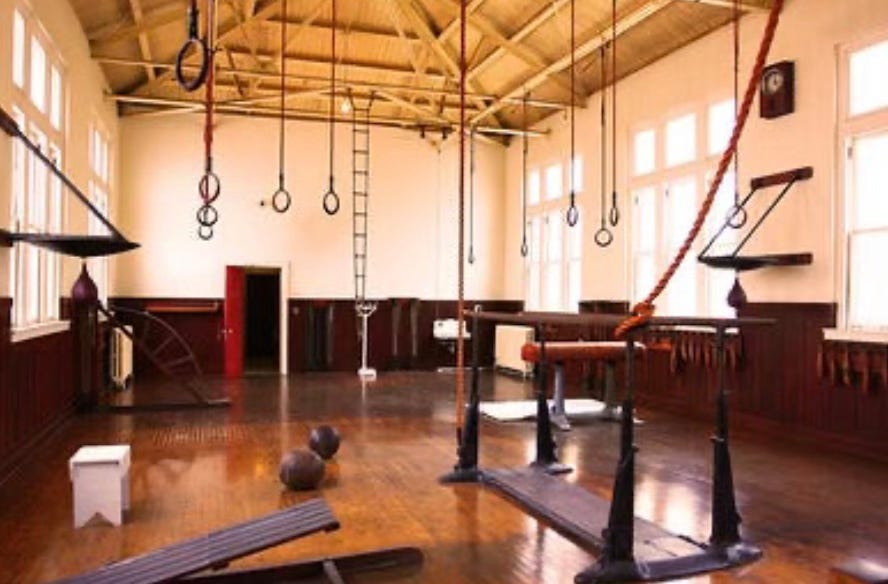

Tree World is not well-represented in modern gyms, but it was not always this way. Check out this pic of an old-timey gymnasium, which offers numerous affordances for climbing movements.

Many forms of resistance training replicate the basic compound joint movements used in climbing. Pull-downs, rows, presses, step-ups, and squats are obvious examples. These movements are an excellent way to get many of the benefits of climbing without the downsides of having to find a tree, or possibly fall out of a tree and kill yourself. The difference is that these gym movements involve less variability and full-body coordination.

By contrast, climbing movements always involve both the upper and lower body. For example, pulling with one arm is frequently coordinated with pushing of the opposite side leg, a movement rarely seen in the gym. Fortunately, this movement and other simple body weight challenges are easy to reproduce without a tree, and with a minimum of equipment, such as a box, pull-up bar, and TRX straps. I will provide numerous examples of similar exercises in the climbing section. Most can be done at home.

3. Bipedal World

“Bipedal World” encompasses the fundamental locomotive movements for humans: walking, running, jumping, and pursuit/avoidance (agility). A typical day in the life of a hunter-gatherer will likely involve some amount of each of these movements, developing a wide range of fitness qualities.

High volumes of walking develop metabolic health. Moderate volumes of running at slow pace and short bursts at high pace build cardiovascular health and fitness. Very brief amounts of sprinting or jumping develop power. Constantly navigating variable terrain while walking, and occasionally moving at high speed to avoid or pursue animals builds agility.

Children also show highly variable patterns of locomotion. Every day brings jumps, games of tag, lots of slow walking and movement, and occasional bursts of higher speed. No dramatic huffing and puffing, just lots of varied activity throughout the day.

The modern approach to training the fitness qualities of Bipedal World tends to differ in several respects. It is generally lower volume and higher intensity, because people have less time to exercise. It is also less variable and more specialized, with the prototypical example being someone who runs at the same moderate pace, for the same distance, on flat surfaces, every day. For athletes who include a variety of locomotive challenges in their program, they are often compartmentalized. Long slow distance one day, sprints on another, agility in a separate session. This might be highly effective for measuring progress, but also makes planning complex, and often leads people to focus on one quality while ignoring others.

Another feature of modern exercise is the ability to separate the physiological from the musculoskeletal demands of locomotion, through equipment like bikes, elliptical machines, or stairmasters. This allows people to obtain the cardiovascular benefits of bipedal locomotion while sparing their joints the stress of running. This is a wonderful thing! For example, as far as the heart and lungs are concerned, biking is Bipedal World.

These modern methods for training locomotive abilities are often good choices given modern time and environmental constraints. But recognizing the differences from natural movement patterns helps us identify ways to make improvements.

For example, people focused on intense exercise may fail to include walking as part of their exercise plan, simply because they don't appreciate its unique benefits. In some cases, going for a relaxing walk would be more productive than another round of sprints. Conversely, people who don't consider themselves athletes often underrate the benefits of doing at least the easiest versions of more intense movements like jumps and sprints, which are often avoided completely.

You don't need to visit a gym to access Bipedal World, you just need to step outside.

4. Tool world

Tool World is not defined by a physical environment, but by our intention to move objects.3 In ancestral settings, the key movements are lifting, carrying, throwing, digging, chopping, and cutting.4

These movements build on the foundation of more primal patterns. Carrying is essentially loaded walking. Lifting is standing from a squat plus the “tree movement” of pulling with the arms. Throwing or chopping movements combine compound joint pushing movements of the arm (developed for climbing and crawling) with the rotational movements of bipedal gait.

These are diverse movements but share some common elements. First, they require work from the hands, naturally building grip strength, which is strongly associated with overall strength and mortality.5

Second, tool movements tend to be high frequency and therefore low intensity. Thus, lifting rarely involves the near maximum efforts seen in gyms with barbells - there's little reason to lift something you can't carry for a distance.

Third, tool movements often involve skill, and therefore challenge the mind as much as the body. Tellingly, when kids play with objects on a playground, such as sticks for digging or swordplay, or rocks for throwing, they are challenging their skill, not their strength.

In modern gyms we see different patterns in the way people move objects. Lifts tend to be relatively high intensity and low volume. Many spare the grip in favor of working the "target" muscles. Barbells are moved at weights that would be unliftable in natural settings that don't provide objects with convenient grips.

While these modern approaches excel at building strength efficiently within time constraints, the ancestral pattern suggests they are probably not compulsory. Instead, you can build a healthy level of functional strength by climbing movements, or taking advantage of the many opportunities for handling heavy objects that are available at home—carrying groceries up stairs, working in the garden, or using simple equipment like kettlebells or sandbags.

Summary and takeaways

The “four worlds” idea gives us a rough but simple way to categorize natural human movement patterns. A typical ancestral movement “diet” probably looked something like this: several hours daily in various ground positions, 5-10 miles of locomotion at varied speeds (some of it while carrying moderate loads), climbing activities 2-3 times per week, and working with the hands throughout the day.

Children naturally gravitate toward a similar balance between the different worlds, and this can be seen by looking at the layout of a playground. The sandbox is for ground flow, the monkey bars and climbing structures are “trees”, the open space is for varied locomotion, and there are sticks, balls, toys and rocks for work on manual skills.

These activities create complementary fitness benefits: ground movements develop lower body and spinal mobility in flexed positions; tree movements build upper body mobility in extended positions and full body strength; bipedal movements provide comprehensive conditioning across all energy systems; and tool use adds functional challenge while developing grip strength. Perhaps most importantly, physical activity is distributed at low intensity throughout the day, not confined to a narrow window of extreme exertion.

We don’t need to replicate these patterns to be healthy. In fact, humans are remarkably adaptable creatures who can flourish under diverse circumstances. Further, modern environments offer many advantages over African savannas, and gyms provide safe, efficient opportunities for movement that are clearly preferable to many ancestral challenges.

That being said, ancestral patterns of movement provide a useful reference point that can help you decide how to make beneficial adjustments to your current exercise plan, by adding exercises that are missing, de-prioritizing less essential exercises, or reclaiming lost abilities through regression to more fundamental worlds of movement.

Further, connecting movement to environment helps you become more aware of movement opportunities throughout your day. As you explore each primal movement pattern in subsequent chapters, consider where you might practice them in your daily environment. Creating these associations between places and movements helps establish consistent habits.

The chapters ahead will examine each world in detail, beginning with the most fundamental: movements performed close to the ground. Ground-based patterns form the foundation for everything else we do, yet they're often the most neglected in modern life. Fortunately, they're also the easiest to begin practicing immediately—no equipment required, just a willingness to get reacquainted with the floor.

We’ll start with rolling, one of the simplest movements possible. Expect a chapter on this movement along with exercises soon.

Footnotes

Raichlen, D. A., Pontzer, H., Harris, J. A., Mabulla, A. Z. P., & Marlowe, F. W. (2020). Sitting, squatting, and the evolutionary biology of human inactivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(16), 9215‑9223.

Venkataraman, V. V., Kraft, T. S., & Dominy, N. J. (2013). Tree climbing and human evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(4), 1237‑1242; Kraft, T. S., Venkataraman, V. V., & Dominy, N. J. (2014); A natural history of human tree climbing. Journal of Human Evolution, 71, 105‑118; Berbesque, J. C., Marlowe, F. W., Wood, B., Crittenden, A., Porter, C., & Mabulla, A. (2014). Honey, Hadza, hunter‑gatherers, and human evolution. Journal of Human Evolution, 71, 119‑128.

“Tool world” is not a great name for these movements because some of them (e.g. throwing and carrying) don’t involve tools. I considered “object world” or “manual world.”

Pontzer, H., Raichlen, D. A., Wood, B. M., Mabulla, A. Z. P., & Marlowe, F. W. (2015). Energy expenditure and activity among Hadza hunter‑gatherers. American Journal of Human Biology, 27(5), 628‑637.

Celis‑Morales CA, et al. Associations of grip strength with cardiovascular, respiratory and cancer‑specific incidence and mortality, and with all‑cause mortality: prospective cohort study of 502 293 UK Biobank participants. BMJ 2018; 361:k1651.

Hi Todd, a dimension of movement capacity I've been aware of lately relates to expression (gesturing, caressing, dancing). I'm curious where it fits into these worlds.

In my own shoulder rehab, I've been playing around with the idea that regaining a "normal" feeling limb isn't just about range of motion or strength to push/pull/grip. There's a sense that it's not at full capacity until I can use it to articulate feelings. I discovered this at a dance class where I was able to play with all kinds of strange angles and wild gestures, not for practical "tool" purposes, but for aimless expression. It was like the shoulder-map in my brain wasn't fully re-engaged till I added this to the movement diet.

What a pleasure to discover the book chapters bu chapters, the categorization is so clear and clever,

This quest to the healthy movement is very exciting