Homunculus update

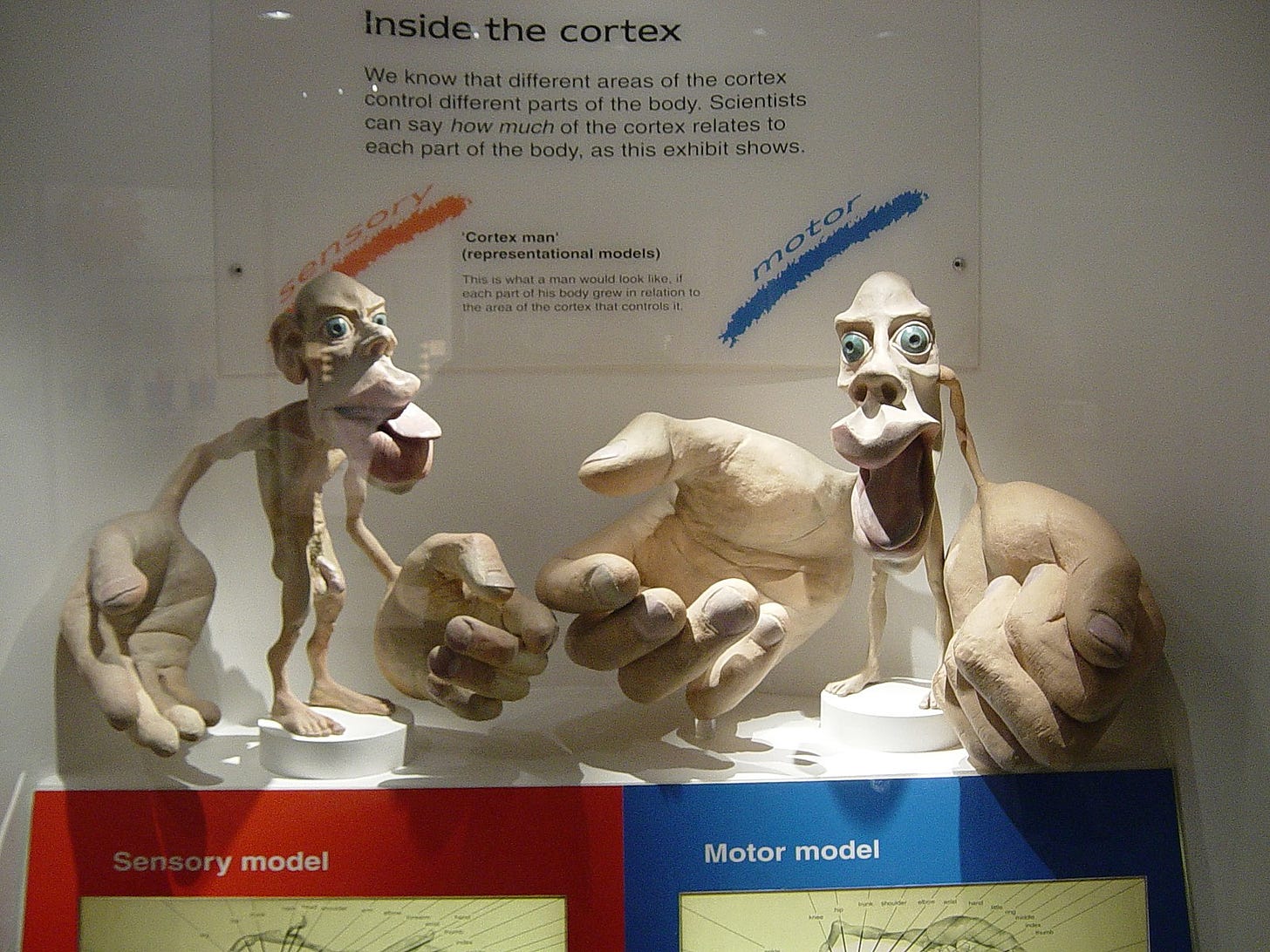

The homunculus is a classic neuroscience diagram that depicts the brain areas that perceive and control the different body parts. It illustrates the fact that we have larger brain areas devoted to body parts that have more differentiation in perception and control, such as the hands and face.

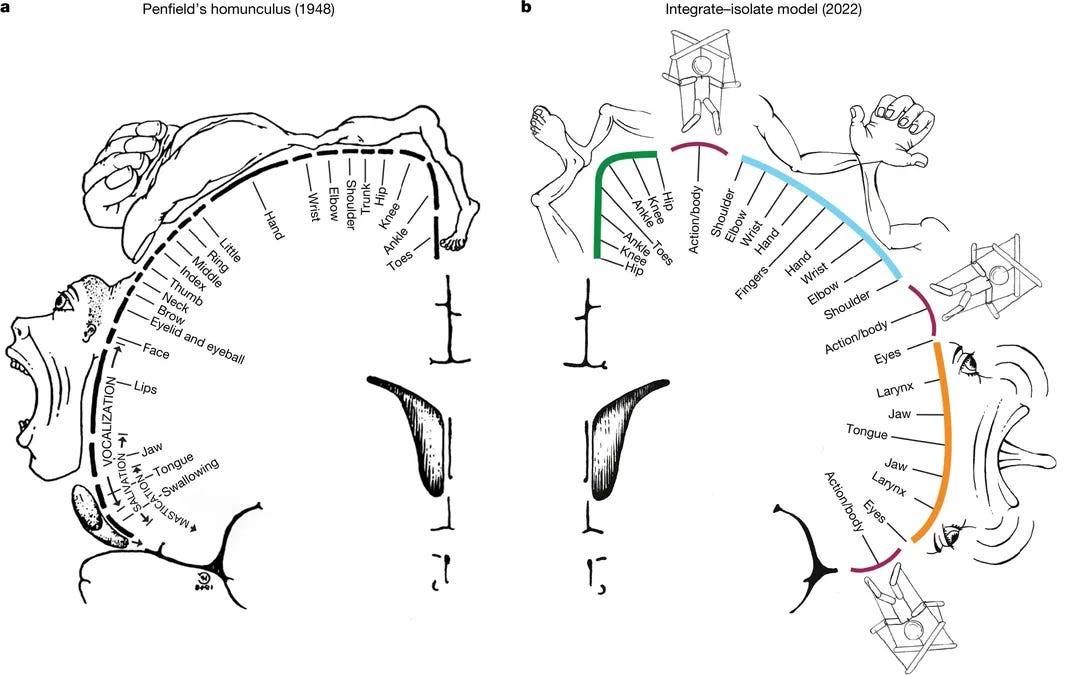

These areas has been well-mapped for decades, but a new study made some updates to the motor homunculus as shown below.

The updated map includes three new areas, depicted in red. These separate the primary motor cortex into three sections: lower body, upper body/torso, and head. The red areas are labelled intereffector areas, and probably function to coordinate movements between the different sections. These areas are not present in new borns, start to develop at 11 months, and are mostly mature in nine-year olds.

Another new finding is that within each body section, the outermost body part is in the center, with inner parts radiating outwards. Thus, the fingers and toes are in the center of the lower and upper body sections, with the hips and shoulders on the outside. I wonder whether the central location of the fingers and toes has something to do with the fact that these are the areas where we interact with the environment.

The intereffector areas may also be involved in pain perception, and further research will look further into this connection.

Reminder: New class on full body mobility

A reminder that the new class on reaching starts next Sunday. Each lesson is all new! Click here to sign up and here for more info.

Great apes reach momentary altered mental states by spinning

That is the actual title of new scientific study. The evidence? Researchers browsed YouTube videos like this:

And this:

So why do the apes do this? Here’s the explanation from the paper:

When spinning, the apes achieved speeds sufficient to alter self-perception and situational awareness that were comparable to those tapped for transcendent experiences in humans (e.g. Sufi whirling), and the number of revolutions spun predicted behavioural evidence for dizziness. Thus, spinning serves as a self-sufficient means of changing body-mind responsiveness in hominids. A proclivity for such experiences is shared between humans and great apes, and provides an entry point for the comparative study of the mechanisms, functions, and adaptive value of altered states of mind in human evolution.

So the apes were looking for self-transcendence? Hmm. I think a better explanation was that they were playing. Physical play often involves movements that create some kind of risk. The animals benefit from engaging with this risk because it develops their movement skills and confidence. Here’s a good quote from the psychologist Peter Gray:

In their motor play and rough-and-tumble play, juvenile mammals appear to put themselves deliberately into awkward, moderately frightening situations. . . . When they leap, for example, they twist and turn in ways that make it difficult to land. They seem to be dosing themselves with moderate degrees of fear, as if deliberately learning how to deal with both the physical and emotional challenges of the moderately dangerous conditions they generate.

For more on risky play, here’s a previous post.

Can exercise strengthen intervertebral discs?

Stress from exercise can either build the body up or break it down, depending on its frequency, volume, intensity, and type.

We have a good idea about the kinds of stresses that make muscles stronger, because the health and function of muscles is fairly easy to measure and assess. What about intervertebral discs? It's hard to gather evidence about how they respond to stress because of their deep location in the body.

Degeneration of the disks is generally overrated as a cause of back pain, but it can be a contributing factor, so we would like them to be as healthy as possible. It would therefore be good to know something how they adapt to physical stress, and what kinds of exercise tend to build them up versus break them down.

This paper (h/t David Poulter) examines the available evidence and tries to make recommendations. It looks at studies examining cadavers, the disc health of various kinds of athletes, and the response of animals to exercise. Here are some interesting findings.

Studies on cadavers suggest that discs can withstand high loads of axial compression, but are more likely to be damaged when these loads involve end-range flexion. Torsion and rotation may damage the disc through shearing forces.

Studies on disc cells suggest that they respond positively to dynamic axial loading. Static loading and immobilization are not beneficial.

Disc degeneration is more common in sports involving the risk of traumatic injury (e.g. gymnastics and football), repetitive loading of the spine in the end range of flexion and extension (e.g. gymnastics, cricket, weightlifting, and rowing), repetitive loading into rotation (e.g. baseball and swimming) and frequent unpredictable landing forces (e.g. volleyball and horseback riding.)

Running sports appear to be either not detrimental or beneficial.

Higher levels of sport participation are associated with more damage. But too little physical activity is also a problem:

It appears there is a U-shaped relationship between lifetime physical activity and IVD degeneration: sedentary occupations and heavy occupations can increase the risk of IVD degeneration [50], with the least amount of degenerative changes in people who performed moderate levels of physical activity.

Several study on animals have shown beneficial effects of running on disc health.

From this evidence the authors concluded that some forms of stress on the discs build them up, and others break them down:

Overall, this body of literature helps to underscore the point that the IVD does adapt to loading and that this response may ‘strengthen’ the IVD, but that loading can also have negative (catabolic) effects

Here is a summary of the types of loading that appear to be more beneficial:

loading types that are likely beneficial to the IVD are dynamic, axial, at slow to moderate movement speeds, and of a magnitude experienced in walking and jogging. Static loading, torsional loading, flexion with compression, rapid loading, high-impact loading and explosive tasks are likely detrimental for the IVD. Reduced physical activity and disuse appear to be detrimental for the IVD.

All of this data supports the idea that walking and running at a moderate level of activity are the best exercises for keeping the discs healthy.

From an evolution perspective, this is exactly what we would expect. Like all other animal, human animals are designed for locomotion.

Update: I forgot to point out that although many sports are associated with higher risk of disc damage, this doesn’t imply that you should avoid them or fear them! In many of these sports, back pain levels remain low, and it is extremely common for atheists to have lots of tissue damage and no pain. For many individuals the general health benefits (and indeed pain killing benefits) of exercise will outweigh any damage it does to the body.

Another reason to walk more

If you wanted to predict whether someone had anxiety or depression based on their Fitbit data, which metrics would be most useful in making your prediction? Would you look at steps per day, active minutes per day, total calories burned, or average heart rate?

According to this study, the answer is steps, and it’s not even close.

More evidence that walking is the best form of exercise.

More on AI for medicine

When AIs eventually get better than humans at diagnosing and recommending treatments for medical problems, the humans will still have an advantage because they have more empathy, right? Maybe not.

In a new study, researchers at UCSD randomly selected 195 patient questions from a social media forum, and these were answered by ChatGPT and real docs. A panel of health care professionals scored the answers for quality and empathy on a 5-point scale.

In regard to quality, 80% of the ChatGPT answers were considered good or very good, and this figure was only 22% for the doctors.

For empathy, 45% of the ChatGPT answers were considered empathetic or very empathetic, and this figure was only 4.5% for the docs.

For more on the study and what it means, here’s a good article from Eric Topol.