Evolutionary Mismatch, Fibromyalgia, PRP

And other things I read about last month

Here are some more things I read and thought about in the last few weeks.

Chronic pain and evolutionary mismatch

A recent paper argues that chronic pain may be the result of an “evolutionary mismatch.” First a bit of background, and then I’ll get to the paper.

An evolutionary mismatch is defined as “a state of disequilibrium, whereby a trait that evolved in one environment becomes maladaptive in another environment.”

A classic example would be putting humans, who evolved their dietary preferences on the African savannah, into a modern environment with ready access to Twinkies, Fritos and ice cream. Our innate desire to consume foods that are sweet, salty and fatty is adaptive in the ancestral world, and maladaptive in the modern world. Thus, obesity and other metabolic disorders can be considered “mismatch diseases.” They are also called diseases of civilization, because they are almost unknown in hunter-gatherers who live in more ancestral environments. Other diseases of civilization include diabetes, osteoporosis, and tooth decay.

The paleontologist Daniel Lieberman, author of the excellent book The Story of The Human Body, explains that most mismatch diseases occur when:

a common stimulus either increases or decreases beyond levels for which the body is adapted, or when the stimulus is entirely novel and the body is not adapted for it at all. Put simply, mismatches are caused by stimuli that are too much, too little, or too new.

I have always been interested in the question of whether chronic pain involves some sort of mismatch between the ancestral environment and modern environments. One reason is that the modern world is missing an important stimulus that is ever present in the ancestral world – the need to engage in high levels of physical activity to survive. It's plausible that the relative lack of this stimulus in the modern world would increase the risk for developing chronic pain. Check out my podcast with James Steele for more on this perspective.

I previously wrote about another speculative hypothesis: maybe the comfort and coziness of the modern world is somehow unhealthy for us. I was motivated to write this after my experience on a camping trip, where I was beset by a constant barrage of low-level discomforts, like bug bites, scratches, and not having a soft bed to sleep on.

Yes, I was just being a total wimp, but it caused me to speculate that maybe I would have been less wimpy if my life so far hadn’t been so filled with soft and comfy objects like couches, pillows, beds, and fleece. Here in Seattle we always wear fleece, even to weddings. Perhaps there is something about the modern prevalence of fleece, and the relative absence of low level noxious stimuli, that dysegulates the pain system, making it more likely to get reactive in the face of minor insults. In the same way that the immune system needs to be exposed to a certain amount of dirt, maybe the pain alarm system needs to be exposed to regular scratches and bug bites.

Now let’s get to the new paper. It proposes another potentially important difference between the modern and ancestral worlds - the need to get moving shortly after getting injured. If you are living the life of a hunter gatherer, returning to physical activity shortly after an injury is mandatory not optional. So i your back goes out after a hard day or foraging, you might be able to take a few days off to rest. But if you don't get out there hunting and gathering again pretty soon, you will starve.

When you get moving again, this will probably activate the pain inhibitory systems that block the flow of nociception from a damaged area to the brain. And that’s a good thing, because keeping these systems active and functional is necessary to prevent chronic pain. People who suffer from chronic pain have a problems getting these inhibitory systems going.

We would also suspect that the environment that is most likely to activate the most powerful response of the pain inhibitory system is an emergency situation that directly affects survival. And that's the situation that you're in when your belly is empty and you have no fridge.

In the modern world, thankfully, most people (not all!) aren’t under this kind of pressure to move. Their main motivation to get moving after an onset of back pain might come from the tepid, evidence-based recommendations of a doctor, and these are easy to ignore. And even if you do decide to do your exercises, there is an unconscious part of you that can’t help but know that these exercises aren’t necessary for survival. Does this make a difference?

This strikes me as an interesting but highly speculative possibility. And I should point out that it should not cause any of us to think about starving ourselves as a way to get over back pain or other injuries. I should also mention another weakness in this theory. It seems that chronic back pain is not a disease of civilization, as it is common in populations of hunter-gatherers.

Still, an interesting idea.

Shaquan Parson

I just watched Dune, which was excellent. For the sequel, they should hire Shaquan to do some of the fight sequences.

The hips of ultra-runners

A new study finds that the hip joints of asymptomatic ultra-runners don’t look significantly different from those of normal runners and non-runners on MRI. The conclusion:

The findings help correct popular misconceptions that long-distance running damages the hip joints, and therefore should be taken into account when making health recommendations.

How muscle damage gets repaired

Exercise causes microscopic tears in muscles. This study sheds light on how they are repaired. Just a few hours after exercise, the nuclei of the cells migrate along the tube-like length of the muscle cell to the area of damage. When it gets there, it starts issuing commands for protein production to fix the damage. This article on the study discusses some other known features of muscle damage repair: proteins form a protective cap over membranes, and mitochondria soaks up excess calcium released by the tear.

Every step counts

Exercise is like a nutritious food in the pattern of relationship between “dosage” and health benefits. If you are getting zero of a particular nutrient (e.g. vitamin c or iron), then getting even tiny amounts will have huge benefits and probably prevent a specific deficiency disease. Consuming more of the nutrient will continue to promote health, but the benefits of each additional dose will decrease, and then eventually flatline. (At some point taking more of the nutrient might become toxic.)

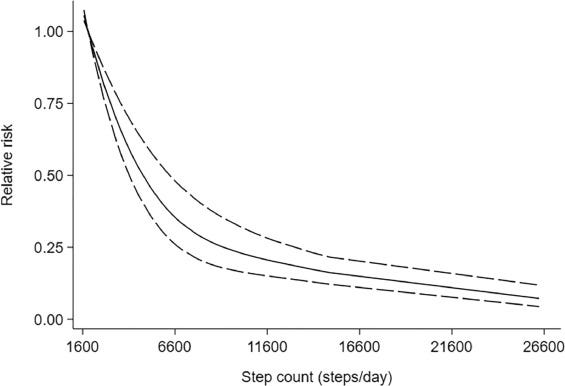

Here’s a chart from a recent study showing this pattern with daily step counts and its effect on reducing the risk of all-cause mortality.

Check out the rapid decline in mortality risk in going from 1,500 to 3,000 steps per day. That's a bigger health benefit than going from 5,000 to 10,000. This should help to dispel the common misconception that walking doesn't start to have any benefit until you get to some magic number like 10,000 steps. Instead, each step counts, and they count even more when you don't do very many of them.

Does platelet rich plasma injection work for ankle osteoarthritis?

According to this study, no.

How can you give fibromyalgia to a rat?

Give them immune cells from a human with fibromyalgia. In a new study, researchers collected IgG samples from patients with fibromyalgia and injected them into rats. They observed the following effects:

increased sensitivity to noxious mechanical and cold stimulation

reduced locomotor activity

reduced paw grip strength, and a loss of intraepidermal innervation.

Importantly, these effects were not observed when the rats recieved blood that was depleted of IgG.

The conclusion:

Our results demonstrate that IgG from FMS patients produces painful sensory hypersensitivities by sensitizing peripheral nociceptive afferents and suggest that therapies reducing patient IgG titers may be effective for fibromyalgia.

More evidence that the immune system plays a big role in chronic pain and disease in general.

I also agree with the Every Step Counts segment. More is not necessarily better. No need to feel guilty that you don't churn up and down the pool for an hour, can't run a half marathon every week, or don't hit the gym everyday. The culture of pride and awe around excessive exercise is really not helpful for most. You can get perfectly fit and healthy, and look your best doing just a little exercise, and you are less likely to get injured. Ever since I read The First Twenty Minutes (Gretchen Reynolds - and I hope the science is still right!) I'm content at mid life doing my 1km in the pool. The law of diminishing returns prevails.

Returning to physical activity soon after injury is a winner for me. I have two stories to tell about this. The first was a few years ago when I suffered nerve impingement in my neck and was strapped up and on high level pain killers (which didn't really help). It took a few months for the pain to subside but I returned to surfing before that occurred. Mostly because the reward from surfing was too great compared to the pain (I'm addicted to surfing). I believe by returning to surfing I taught my body that the pain was ok and tolerable. The neck pain continued to get better, and today although I continue to feel a remnant of it, it does not inhibit my daily life in any way. The second incident was recent. I had a sore back, went surfing, and it became worse. That night I would experience painful back spasms in bed when rolling over, or moving in a particular way. The next day I spent on the bed to rest it. I felt pretty miserable doing that as it was beautiful outside and a day for the ocean. Over the following week I had slow improvement and the spasms subsided, but I was still too sore to surf. At the end of that week I woke up again back at square one with the bad back pain! I spent the day on the bed with anti-inflammatories and felt tired and fed-up. The following day I woke with back pain AND a crick in my neck from sleeping badly! Couldn't believe it. Oh no, another day on the bed.... But I was too miserable at that thought so made myself go to the beach to meet my friends for our regular Sunday ocean dip. My thought process was as the bed rest made me feel worse, I am going to continue as normal, but respectful toward the sore bits of my body. Warm sun, cold ocean water, light body surfing, connection with friends - I could not believe the difference it made to my physical discomfort and mood - all much improved! My back pain is still there but receding, and I know it will resolve, and I will be surfing again just in time for an upcoming surfing holiday :-).